How I Fixed Monopoly.

A Game Balance Story.

Reading Time: 11 minutes

You mean the classic board game?

That’s the one! When I was little, my family would play Monopoly on New Year’s Eve. Being the youngest of the whole bunch and grabbing every opportunity to play games, I would lie awake even before Christmas thinking of which strategy would be best and how I could beat my brothers this time.

I’m sure you have your (fond) memories regarding Monopoly. Or at least you’ve played it. What do you think of it?

I think that Monopoly has earned its merits as a classic game that is over a 100 years old and has been sold 250 million times. Because of this, you might say that the game doesn’t need fixing. However, I’m going to propose some modifications anyway…

Why fix something that ain’t broke?

Well… there’s something wrong with Monopoly. Somehow, the game feels broken. For generations, people have been trying to fix this by adding house rules to the game in order to change the game’s dynamics, like game pace, but also to balance the game. Public consensus is that in Monopoly the Orange group (Utrecht in the Dutch version) is overpowered as well as the Dark Blue group (Amsterdam). Utilities (Elektriciteitsbedrijf and Waterleiding) on the other hand are not worth the investment. Also, many people feel that the starting player has a huge advantage.

It’s only natural to try and fix Monopoly. We want to balance games from an inherent sense of justice. We want the games we play to be fair, i.e. everyone playing the game should have an equal chance to win. Otherwise, it doesn’t feel right. If a player knows that one strategy is better than all other strategies, the player will generally tend to go for that winning (dominant) strategy. It shows that that player ‘gets’ the game. After a short while, however, this causes the game to stop being fun. The challenge has been completed and the player moves on to the next challenge. No, we want games to be exciting. Excitement gets our dopamine running and makes us happier.

But how come Monopoly is so successful then?

Other than its balance, Monopoly does a lot of things right. Its mechanics are simple and we love the luck of the draw. Everyone goes ecstatic when someone lands on a ‘cheap’ spot between hotels against all odds. The game does things to our mind and lets the dopamine flow. When the game first came out, Monopoly was a board game revolution. Back in the early twentieth century there weren’t a lot of family tabletop games and this game gave families a reason to enjoy playing games together.

However, I honestly believe that if Monopoly had been a well balanced game, it would be much more fun to play, because players would be able to try out more strategies and would want to replay the game. After losing a game of Monopoly, have you ever had the feeling that you wanted to play another, and another, and another?

Being a professional game balancer, my mission is to balance games, in order to make them more fun. If games are even more fun to play, I feel that the world is a better place. On top of that, players play balanced games longer, so game studios making those games get more revenue. Besides, they save a lot of time tweaking.

Aren’t there a million things you could adjust?

Yes. In terms of game design there are numerous features that you can adjust in a game like Monopoly, for instance dynamics like game pace (how fast does the game develop) or game length. You might consider changing the number of properties or altering the Chance (Kans) and Community Chest (Algemeen Fonds) cards.

These are game design considerations, however. When looking at game balancing, we can keep it a lot simpler. Actually, let’s keep the design as it is and make sure that game pace and length remain the same. All properties remain in place and the Chance and Community Chest cards won’t change. In fact, let’s only change the rents of the properties, and add (and slightly adjust) one (house) rule with respect to tackling the starting player advantage.

So, how do we set this up?

Time to get technical. For each property, we want to know its return on investment (ROI). How much do I get back for each dollar (or euro) I invest in a property or house? To find the ROI of a property, we can look at the money you’ll earn when a player lands on your property and compare that to how much you’ve invested. For instance, for Mediterranean Avenue (Dorpsstraat), you’d have to invest 60 to buy it. When someone lands on it, you get 2 back. The resulting ROI is 3.33%.

Next, let’s find out how many times players actually land on each property. For this, we’ll need to run a partial simulation. We’ll create a board consisting of 40 spaces and a player that rolls 2 dice and goes around the board. Then, if that player lands on a property, we’ll count that hit. In the end, if we divide all those hits by the average total number of hits for all properties and by the total number of spots (40), we’ll get the normalized amount of hits each property gets. Each number represents the likelihood that a spot will be hit, 1 being average. To get an accurate number, the simulation needs to include Chance and Community Chest cards, jail and wanting to stay in jail near the end of the game, and a total game time of about 30 turns in which rolling doubles creates an extra turn. Then we let the simulation run 1 million of these ‘games’. In the simulation, this only takes 2 seconds, but in real life, this would take an astonishing 7 years! The Hit Rate Heat Map shows a heat map of the hit rates of each property.

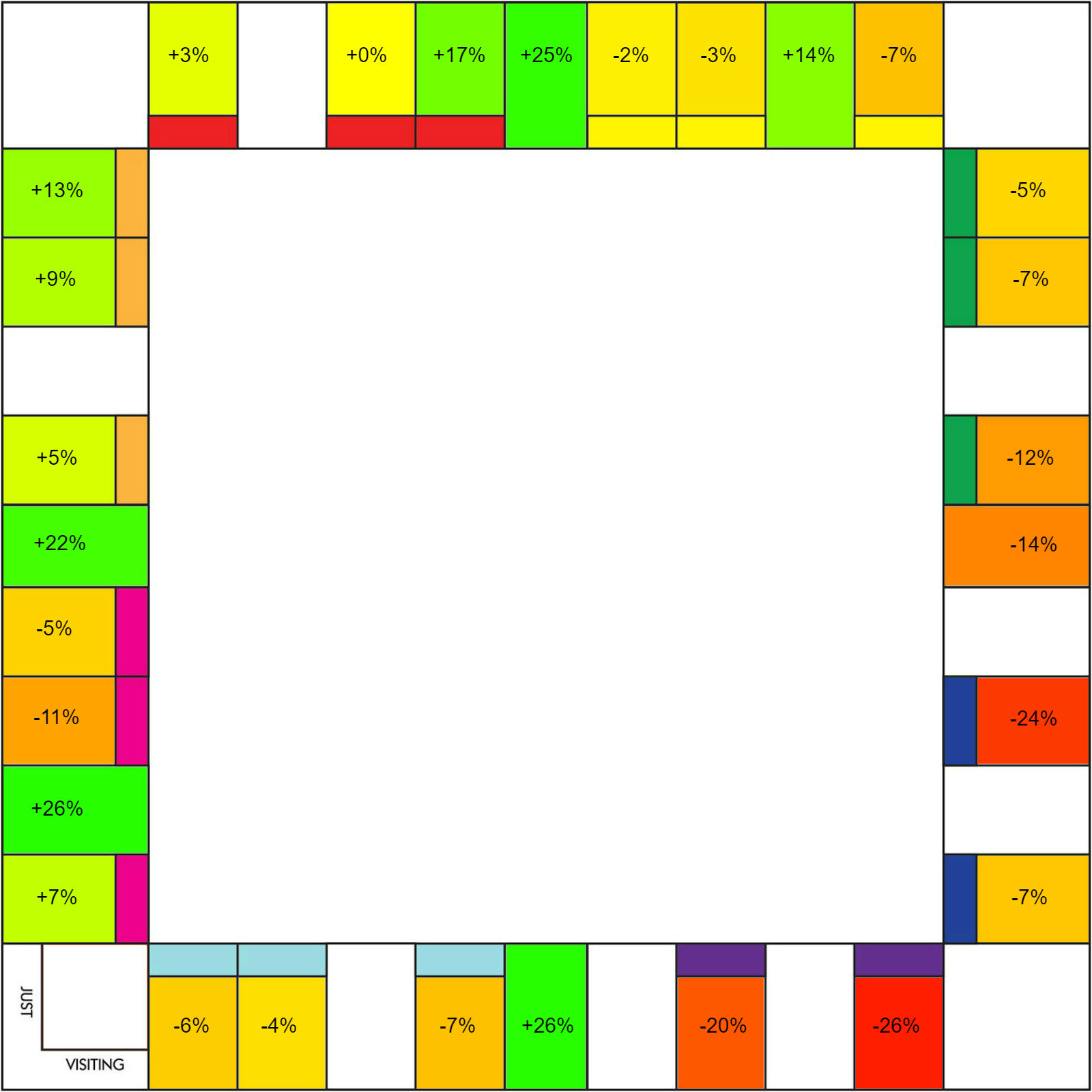

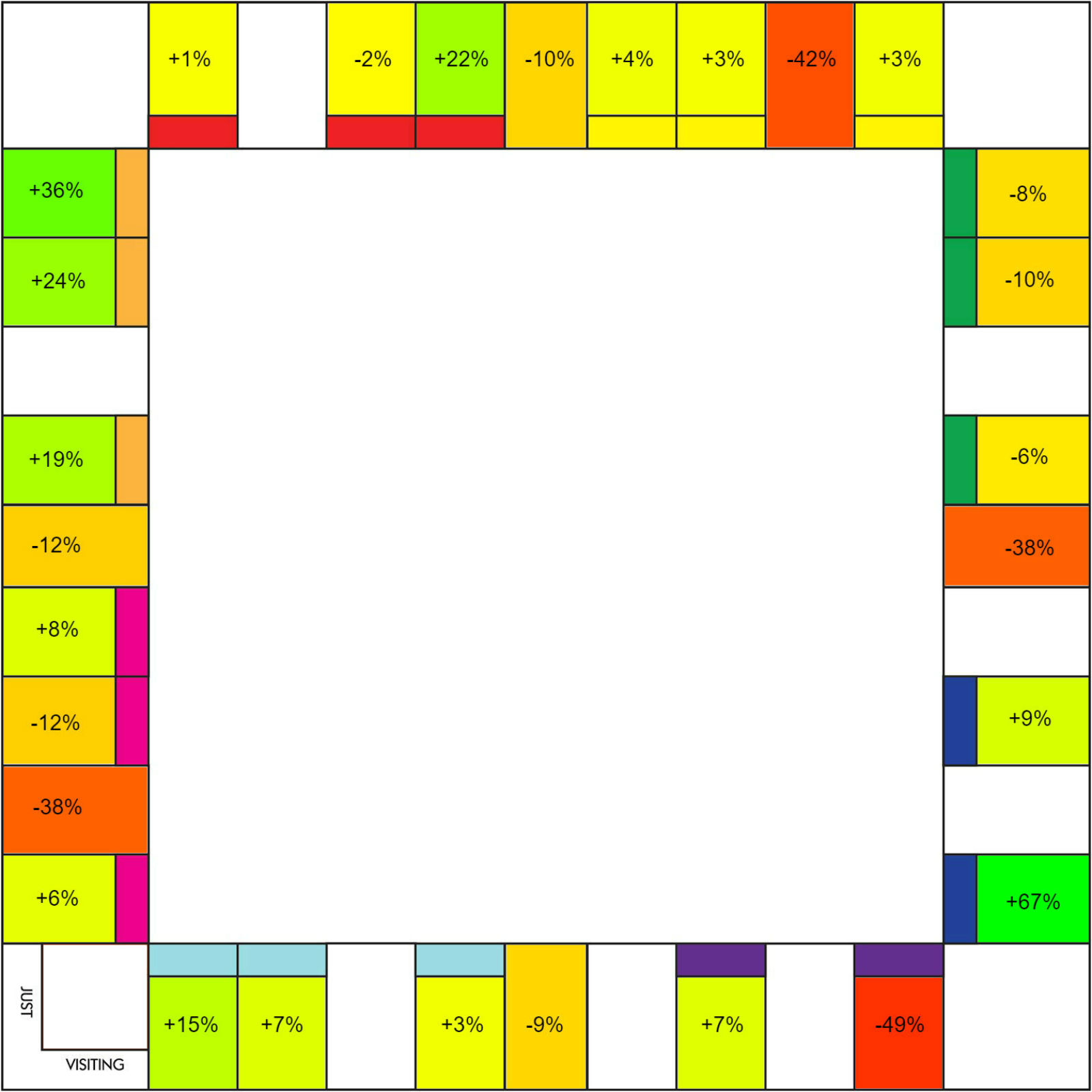

Now, let’s multiply the normalized hit rate we found in the simulation with the ROI in order to get the ‘actual’ ROI for each property and all amounts of houses. As we can see in the Average ROI Heat Map, the colors differ a lot, which indicates imbalance in the game. Orange (Utrecht) and Dark Blue (Amsterdam) are indeed the towns with the highest ROI (greenest), which means that if you own one of these towns, you’re more likely to win the game. We were right on that! Balancing this game means that we have to turn the color of every property of the Average ROI Heat Map into bright yellow.

Hit Rate Heat Map.

The greener the property appears, the more likely a player will land on it. The more red it appears, the less likely.

Average ROI Heat Map.

The greener the property appears, the more the owner will earn (relatively) if someone lands on it. The more red it appears, the less the owner earns.

Let’s start balancing!

To make a start towards perfect balance, let’s redistribute these numbers evenly among all properties, so each property has the same ROI. Each property should have a ROI based on the normalized hit rate. In other words, if you land on a specific property more often, you have to pay less than for a specific property with a lower hit rate. Makes sense, right? Oh, and let’s also compensate for the number of properties per town, because it’s easier to collect 2 streets than 3.

Railroads and Utilities work a bit differently than the colored properties, but we can use a lot of the same techniques. The main difference is that instead of building a house to increase the rent, you have to acquire a property of the same type to do so. However, this increases the rent for all properties of the same type instead of one. For instance, when buying the second railroad, rents of both railroads increase. When calculating ROI, the trick is to multiply the rent increase with the number of properties that it increased. When balancing, we have to divide it by that number again.

Utilities work differently from railroads in a way that the rent is determined by the die roll of the player landing on it. We’ll calculate that factor by simply dividing the result by 7, since that is the average number that is thrown when landing on a utility. Actually, the average numbers thrown when landing on utilities are 6.895 and 7.087 respectively, depending on their location.

Now that all values are balanced, we’re done, right?

Almost. The numbers are balanced, but do not yet feel right, because the rents are strangely distributed within the properties. To fix that, let’s look at the factor with which the original rent increases when houses are added. Since the properties themselves are already balanced, let’s redistribute the numbers within each property to match the original rent increase factors.

One more thing. In the original game, the last property of a town has all values increased by an average factor of roughly 22% as compared to the other properties, so let’s calibrate for that too, to give the balanced numbers a real Monopoly feel. We can do this calculation separately, because you need to have all properties of one color to start building houses. Therefore, it doesn’t matter how the numbers are distributed among one color group. The tricky part is that properties still have different hit rates, so I created a formula that calculates the right numbers.

Finally, let’s round all rents to the nearest 5 to not prolong each match by 20 minutes for sorting money…

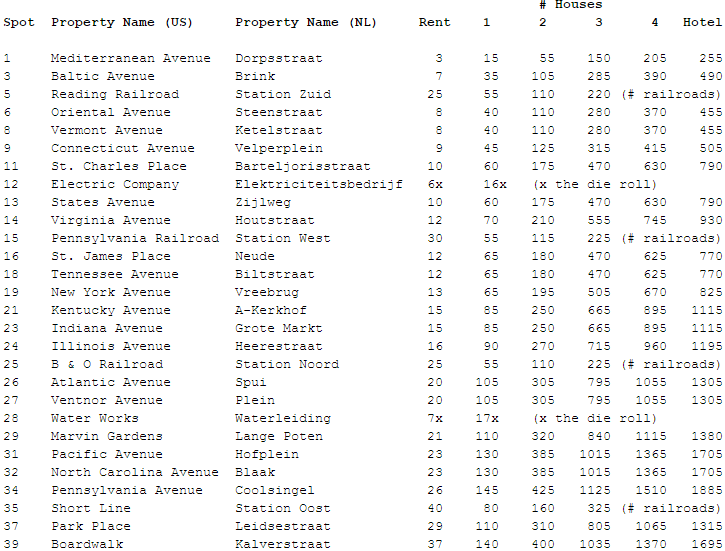

We now see in the list of the Balanced Rents that the rents of the utilities are more than twice as high as they were originally. We were also right on this one!

Balanced Rents.

These are the numbers Monopoly should have for all properties to be equally balanced.

How do we fix the starting player advantage?

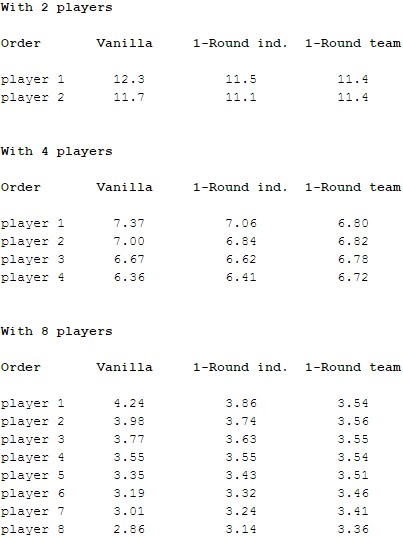

With the original rules, the starting player gets a huge advantage with respect to buying properties, simply because he/she lands on them first. Let’s run the numbers! We’ll run that simulation again, but now we let multiple players run around the board simultaneously and let them collect properties. Let’s do this for each number of players for which Monopoly was designed (2-8).

Now, let’s try this again with adding a house rule that prohibits buying properties during the first round. You’ll see in the House Rules figure below that the numbers get better already, but still are quite off. Besides, this house rule makes the first few rounds of the game a bit boring.

So let’s try something different. Instead of forbidding everyone to buy in their first round, we’ll just prevent them from buying for as long as no one has completed the first round. The rule now reads: “All players may only start buying properties when any one player has passed Go or landed on Go”. The House Rule figure below shows that the numbers have become quite balanced now as the number of properties each player gets on average are very close together, so I would add this rule to the standard rules in addition to the change of rents.

Other house rules like “No auction” or “Landing on Go pays double” don’t really touch the game balance.

As our gut feeling told us, we needed a house rule to balance the game and it was only a little bit different from the one the numbers told us to use!

House Rules.

For 2, 4 and 8 players this figure shows the number of properties a player gets on average depending on the order of play. Player 1 is the starting player, player 2 starts second, etc. The column ‘Vanilla’ indicates play without house rules, while ‘1-round ind.’ and ‘1-round team’ represent the existing and the proposed house rules.

Doesn’t balancing make the game flat and boring?

No, it actually makes the game more interesting. After balancing, the properties have an equal average ROI, but other (random) situations in the game make the ROI in a particular situation go up (or down). For instance, when 2 players are lined up in front of your properties and have a large chance of landing on one of them, the ROI goes up.

Balancing this game makes in-game choices more interesting, because reacting to specific situations is now more important than making that one move that is always the best one regardless of the situation, while still maintaining that classic feeling of randomness and having a chance to win even in case your game skill might not be as high as that of your competitors.

This doesn’t mean that we can turn Monopoly into a ‘good’ game all of a sudden; it’s still far from perfect. With the knowledge we have now about game dynamics and player psychology, I’d design it such that players would have fundamentally different choices with respect to choosing a strategy. But however flawed, I believe that Monopoly has played an important role in the development of the game industry by paving the way for games with more sophisticated dynamics than existed before in family board games. For instance in the 1950’s Scrabble and Risk were great hits, leading to an explosion of choices in games available now, including digital games. Just like Monopoly, however, lots of these newer games are imbalanced, calling for experts on the matter, like me!

Players deserve awesome game experiences!

Gut feelings of players are often right. People feel imbalance and either want to fix it or play another game that is more balanced. Like Monopoly, a game can still sell very well, while being imbalanced, although a game will never sell well because of its imbalance.

I believe that time of players is better spent when playing balanced games, in which everyone gets a chance. Those games tend to be more exciting, while game results are closer together. More dopamine will be released, making players and the ones around them happier. My goal is to make that happen and let each game experience be awesome!

About the author.

Johan van der Beek graduated in Artificial Intelligence (Master’s Degree) in Amsterdam in 2007 after creating cooperative squad behavior in Killzone 2 for Guerrilla Games. He left the gaming industry to focus on creating and implementing smart parsers, AI systems and algorithms for several non-game projects. In 2011 it was time to move these techniques into the gaming industry. Via game design studies and working as a (serious) game designer in simulation and game studios, he now balances and calculates game models using AI and simulation techniques at Ludible – Automated Game Balancing as a freelancer.

Johan van der Beek graduated in Artificial Intelligence (Master’s Degree) in Amsterdam in 2007 after creating cooperative squad behavior in Killzone 2 for Guerrilla Games. He left the gaming industry to focus on creating and implementing smart parsers, AI systems and algorithms for several non-game projects. In 2011 it was time to move these techniques into the gaming industry. Via game design studies and working as a (serious) game designer in simulation and game studios, he now balances and calculates game models using AI and simulation techniques at Ludible – Automated Game Balancing as a freelancer.